by E A S Sarma, former Secretary to Government of India

16/02/2022

“The sweeping, ill-advised disinvestment policy announced by the NDA government in December, 2021 has put most of the national wealth on a distress sale. The few oligarchs who fund the political parties and issue diktats on policy are waiting with their war chests of funds ready to buy the Central Public Sector Enterprises (CPSEs) for a song, along with their enormous wealth.”

“What the NDA government is consciously doing is to increase concentration of wealth among a few influential business houses and widen the income disparities in the society, robbing the poor further, to enrich the oligarchs. If this process continues long, we will soon revert to the erstwhile East India Company days, pushing back the hard-earned independence of the country into the hands of a few influential business conglomerates.”

2021 Disinvestment Policy:

The sweeping, ill-advised disinvestment policy announced by the NDA government in December, 2021 has put most of the national wealth on a distress sale. The few oligarchs who fund the political parties and issue diktats on policy are waiting with their war chests of funds ready to buy the Central Public Sector Enterprises (CPSEs) for a song, along with their enormous wealth. The whole exercise is to be completed in a couple of years and those CPSE heads who fail to cooperate will be summarily removed, with the bureaucrats of the concerned Ministries taking over the CPSEs. The rush will ensure that competition is choked for the oligarchs to corner most CPSEs cheaply.

There will only be a “minimal presence” of the CPSEs in the “strategic sectors” ((Atomic Energy, Space, Defence, Minerals etc.), while those in the “non-strategic” ones (other than a handful of non-profit CPSEs) will all be sold.

“Non-core” land assets of all the CPSEs and most other valuable assets in the public sector will be “monetised”, a euphemism for outright privatisation.

The following three regressive clauses make sure that only the chosen few get the CPSEs without strings.

- Well run CPSEs who can readily take over those on the anvil of privatisation cannot bid for them, which eliminates them from competing with the private bidders.

- The bidders need no prior experience to be able to run the acquired CPSEs.

- The bidders need no prior experience to be able to run the acquired CPSEs.

Many CPSEs to be disinvested have highly valuable land assets; they have invested heavily on R&D effort; acquired highly valuable intellectual property rights; they provide strategic services for defence, ISRO etc.

CPSEs vs Private companies:

Unlike private companies, the CPSEs are entities set up under Article 19(6)(ii) of the Constitution. Under Article 12, they are deemed to be a part of the government. While they are also companies under the Companies Act, engaged in business, their primary role is that of an instrumentality of the government in fulfilling the welfare mandate laid out in the Directive Principles. Also, they are enjoined upon by Article 16 to provide reservation in employment for the SCs/STs/OBCs. Reservations not only provide employment but they also empower those disadvantaged sections. As of now, there are 9.19 lakh regular employees, out of whom 4.6 lakh employees belong to the SCs/STs/OBCs. Out of the total number, 3.46 lakhs are in supervisory cadres. Among them, 1.5 lakhs belong to the SCs/STs/OBCs. Disinvestment of the CPSEs will not only bring uncertainty in the lives of these employees but also close the avenue for future affirmative action.

In addition, the CPSEs play a crucial role in building India’s self-reliance in different sectors. Many of them have invested heavily in R&D and acquired intellectual property rights. They provide strategic inputs for defence, space and other sensitive sectors. During calamities, the government depends heavily on the CPSEs for providing emergency relief for the affected. During the current pandemic, it is widely known how the public hospitals provided affordable emergency healthcare services, while private hospitals, driven exclusively by profit motive, mercilessly fleeced them. Overcrowding of the public hospitals during the pandemic clearly showed how larger investments in public healthcare facilities would have benefitted the people more.

To measure the value of the CPSEs in terms of their profitability alone would therefore be over-simplistic. Valuation based exclusively on the basis of CPSEs’ profitability would thus be misleading and lead to their undervaluation, apart from the fact that it is never easy to replace them as social security providers.

It is not as though the CPSEs are not run efficiently. Many of them compete with their best global counterparts.

Out of the 256 CPSUs, which were operating in 2019-20, 171 earned Rs 1.38 lakh Crores of profits. They contributed Rs 3.76 lakh Crores of tax revenue to the Central public exchequer. They paid Rs 72,136 Crores as dividends to the Centre.

Had the government cared to give them professional autonomy, helped strengthen their corporate governance systems and helped prevent political interference, they would have fared much better.

Politics of the private sector– Small vs Big:

At the outset, a distinction needs to be made between the larger businesses and the smaller ones in the country. There are many studies that have shown that millions of small businesses across the country contribute significantly to economic growth. They represent an individual’s enterprise, with robust ability to face risks and carry out their activities with prudence, meeting the day-to-day needs of the Indian households efficiently and at affordable prices. Unfortunately, they do not get the same patronage and protection from the government, that the larger businesses receive as a matter of right. On the other hand, they are subject to harassment by petty bureaucracy, cutting across a number of departments such as the police, the local bodies, the tax agencies etc. It is these small businesses that the government ought to nurture with sensitivity.

In contrast, like anywhere else in the world, there are large businesses, that have acquired enormous clout over the years. In the context of elections becoming increasingly extravagant and electoral corruption increasing, it is the ability of these large businesses to fund the political parties that has enabled them to exercise control over them and their policies.

The role of corporate political donations in Indian politics:

During the mid-sixties, there was a heated discussion in the Parliament, when it came to light that the Cement Allocation and Co-ordination Organisation had distributed nearly Rs. 40 lakhs as donations to some political parties for meeting their election expenses. It came to light that the Congress party received company donations to the extent of Rs 15.5 lakhs during the last quarter of 1966-67. Madhu Limaye, who was an ardent follower of Ram Manohar Lohia, whose name the BJP often invokes, introduced a Private Member’s Bill in the Lok Sabha demanding curbs on such donations, as they tended to taint the electoral process. Meanwhile, the then Congress government, responding to the sentiments of the Parliament, took an immediate decision on its own to impose a ban on company donations to political parties (https://www.thehindu.com/archives/ban-on-firms-funds-for-parties-govt-decision/article21006459.ece). This was the kind of self restraint that prevailed among the political parties at that time.

Later, recognising that political donations from foreign sources could compromise the national interest, the government brought in the Foreign Contributions Regulation Act (FCRA) in 1976, which was replaced later by its successor legislation with tighter norms in 2010.

However, with electioneering becoming more and more expensive and electoral integrity declining, the political parties became more and more heavily dependent on company donations, forcing them to rethink on banning them altogether. The companies would evidently want their pound of flesh, in terms of changes in the laws and the policies to favour them and a regulatory framework in which they could nonchalantly breach the laws to maximise their gains. The first major breakaway from the Limaye kind of restraint was when the Companies Act in 1985 was amended to permit company donations, initially capped at 5%, later relaxed to 7 1/2% of the company’s profits.

Over the years, the political parties’ appetite for funds increased in leaps and bounds, forcing them to explore new avenues. In 2009, they came up with the innovative idea of an “Electoral Trust” as the new vehicle to channel company donations on a much large scale, without attracting tax liability.

Even these new windows for funding did not quench the thirst of the political parties for funds.

They quietly started breaching the firewall set by the FCRA by accepting illegal foreign donations on the sly. Since both the ruling party and most of the opposition were willing partners in the crime, they became brazen and flouted the law with impunity.

However, with the RTI Act coming into operation in 2005, the civil society could readily access the relevant information from the public domain. A PIL on that basis was filed before the Delhi High Court against the two national political parties for the FCRA violations. The court found fault with the two national political parties and ordered the Home Ministry to investigate and take action within six months. Both the parties went in appeal against this before the Supreme Court, where they failed to sustain their case.

Instead of accepting the apex court’s verdict gracefully, the NDA government found a way to circumvent it by amending both the FCRA (1976) and the FCRA (2010) retrospectively to provide them statutory cover for the offences committed. What was distressing in this entire process was that, in order to avoid a Rajya Sabha debate on the proposed change, the NDA government chose the backdoor of the Finance Acts of 2016 and 2017 to push through these regressive amendments.

Not content with this, the NDA government went a step further by removing the existing cap on donations and introducing an opaque system of “Electoral Bonds” as the new vehicle to channel company donations on a much larger scale, without the public knowing where they were coming from (https://thewire.in/politics/fcra-reviving-lapsed-law-amending-retrospectively-trumps-ethical-legal-barriers). It was the ruling party that gained most in this. It was no holds barred for the NDA, which no longer displayed any pretence about clean electoral politics.

Company donations have thus assumed a dominant role in strengthening the nexus between the private companies and the political parties. It is in this context that one needs to view the series of the far reaching measures recently initiated by the NDA government, which included disinvestment of the CPSEs, monetisation of the public assets, dilution of the mineral development legislation, dilution of the environment and the forest laws etc. For once, political ideologies have got subordinated to corporate money power, the public interest becoming secondary. While the political parties may have got elected by the people once every five years, in the absence of any public accountability during the interim period, they merely carried out the diktats of the corporates on a day-to-day basis.

Past track record of disinvestment of the CPSEs and State public sector enterprises (SPSEs):

Hindustan Zinc Ltd. (HZL):

The Vedanta Group (hitherto referred as “Vedanta”) acquired the erstwhile CPSE, Hindustan Zinc Ltd. (HZL) , along with its valuable lead-zinc mines, during the earlier BJP era.. The procedure adopted by the government in selling HZL to Vedanta has since got mired in a serious public controversy, raising questions about its propriety. Even after taking over the HZL, Vedanta failed to improve its performance, especially its copper and zinc smelters at Thoothukudi and Visakhapatnam, which caused toxic pollution, endangering the lives of the people residing in their vicinity. This triggered an intense public agitation at Thoothukudi, which was mercilessly suppressed by the then State government, resulting in the killing of 13 persons and injuring more than a hundred. Vedanta was forced to shut the unit down.

Vedanta also closed down the zinc smelter and the lead units at Visakhapatnam, disrupting the lives of the employees there. The company is also trying to appropriate the large extent of valuable public land acquired for the HZL, when it was a CPSE, for diverting it to real estate activity. In the first instance, since those lands were acquired under the 1894 land acquisition law that permitted such acquisition for a company wholly owned by the government, to transfer it to a private company through disinvestment amounted to a violation of the land acquisition law. Strictly, the public land that is under HZL’s occupation should revert to the State government and eventually to the original land owners. In fact, the original land owners are now demanding that the land in question be returned to them.

Electricity DISCOMs:

The DISCOM franchises given to private companies for more than 15 cities in the past were mismanaged and the franchises had to be revoked. Except causing avoidable disruption to the electricity system in the concerned States, the private companies provided no additional value to the consumers. Privatisation pushed up the prices, without delivering any additional advantage to the consumers or the society at large. Since the selection of the franchisees was based on a dubious parameter known as “aggregate technical & commercial losses”, which bundled together the technical and the commercial losses, privatisation provided no incentive to the private promoter to invest on upgradation of the distribution network to reduce the high technical losses.

Laissez faire policies and the rise of corporate oligarchy in India:

Since 1991, when the “economic liberalisation” programme started in India, privatisation has been given overriding priority, without emphasis on independent regulation, competitive markets and public accountability. This has led to concentration of economic power in the hands of a few, violating Article 39(c) (“The State shall, in particular, direct its policy towards securing …that the operation of the economic system does not result in the concentration of wealth and means of production to the common detriment”). This has consequently created influential oligarchs who could fund the political parties and, in turn, control their policies. The corporate oligarchs gained undue access to precious natural resources like coal and other minerals, resources available with the public sector banks and vast stretches of public lands. In the guise of facilitating “ease of doing business”, at their instance, the successive governments have diluted the environment laws, the laws in place for regulating the development of minerals and so on. When these powerful business houses violated the laws, the government has often chosen to remain passive, instead of enforcing the laws strictly, deliberately ignoring the costs imposed by such statutory violations on the society.

To cite one such case, the Adani Group has built its empire on the basis of highly leveraged funds from the PSU banks (https://scroll.in/article/923201/from-2014-to-2019-how-the-adani-group-funded-its-expansion), which a smaller private promoter would never have been able to. The Group has already cornered 7 airports, 13 ports, several coal blocks, vast stretches of public land and so on.

The Vedanta Group is an MNC, which has also established its large presence in India in iron ore mining and steel, aluminium, zinc, hydrocarbons, power etc. Its name figures among the mining companies prima facie involved in illegalities in iron ore mining in Goa and Jharkhand, as evident from the reports of the Justice M B Shah Commission constituted by the government. The Supreme Court had found fault with the way the Odisha government violated several legislations, including the PESA Act, the Scheduled Tribes And Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition Of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 (or briefly the “Forest Rights Act”) and the environment laws in force, in granting a bauxite mining franchise to Vedanta over the Niamgiri Hill in Lanjigarh/ Ramgarh districts, without taking the prior consent of the local tribal Gram Sabhas. Vedanta has been a large donor of funds to the national political parties. Its name figured in the judgement of the Delhi High Court on the PIL against violation of the FCRA, referred earlier. It is interesting to note that Vedanta is reported to be ready with a Rs 80,000 Crores fund for buying BPCL and other large CPSEs (https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/energy/oil-gas/vedanta-to-create-10-bln-fund-to-bid-for-bpcl-stake-other-assets/articleshow/89019805.cms).

Facile arguments to justify CPSE disinvestment:

NDA government is trying to justify CPSE disinvestment primarily on the ground that it would bring additional fiscal resources to fund several of its social sector schemes. This is a facile argument as explained below.

In the first instance, selling assets, which yield long-term benefits, to bridge an annual fiscal gap is bad in principle. Proceeds from the sale of an asset should be amortised over its economic life and accounted for in the year-to-year financial statements on that basis.

Even assuming that the government is concerned about covering the fiscal deficit, the gap could be narrowed down significantly by pruning unproductive and inessential items of public expenditure. Considering that the income inequalities in the society are widening, the government could resort to redistributive taxation to contain them, which will bring additional fiscal resources. After trying out these approaches, if additional fiscal resources are still needed, the government could raise the same through direct borrowings from the market on more advantageous terms, rather than raising the same through the disinvestment route, as in either case, additional resources come from the same pool of savings in the economy. The disinvestment approach forces the government to undersell its assets and lose its strategic control of the CPSEs that provide a social security cover, on such a wide range

The only plausible reason as to why the government is frantically trying to sell away its CPSEs wholesale is that it is the large businesses that are pressurising it to hand over the wealth of the PSUs before the Parliament polls in 2024.

Minerals- Social control vs private control

Though the 2021 CPSE disinvestment policy recognises the mining sector as a “strategic” sector, there is no clarity in the mineral policy of the government, that looks at the strategic implications of minerals, as explained below.

Minerals being a naturally endowed resources that can get exhausted soon, if we over-exploit them, it is desirable to ensure utmost sustainability in extracting the mineral resources, to the extent possible.

Interestingly, this aspect in fact finds place in the maxims put forward by Kautilya in his Arthashastra (3rd Century B. C.). Arthashastra referred to the importance of mineral wealth for a country and the need to use it carefully. In particular, the Arthashastra emphasised the necessity of conserving “high-valued” minerals (Verse 7-12-13-16), implicitly suggesting the need to conserve them for the future. This bit of Kautilya’s wisdom is conspicuous by its absence in the National Mineral Policy (2019), which does refer briefly to inter-generational equity, but without laying down a strategy for achieving it. In fact, the mineral policy today is to maximise mineral extraction so as to increase its contribution to the economy. Apparently, those who keep reminding us of the ancient culture are blissfully unaware of the ancient wisdom!

Many developed countries are conserving their own valuable mineral deposits and exploiting those located in the developing countries. For example, the US Stockpiling Act of 1979 seeks to stockpile strategic minerals for meeting its national needs. The US, which has one of the largest nuclear power generation capacities in the world, used to depend almost entirely on domestic Uranium in the eighties but has systematically reduced domestic production of the fuel, enhancing its dependence on imports that constitute around 91% of the Uranium used for its nuclear reactors today.

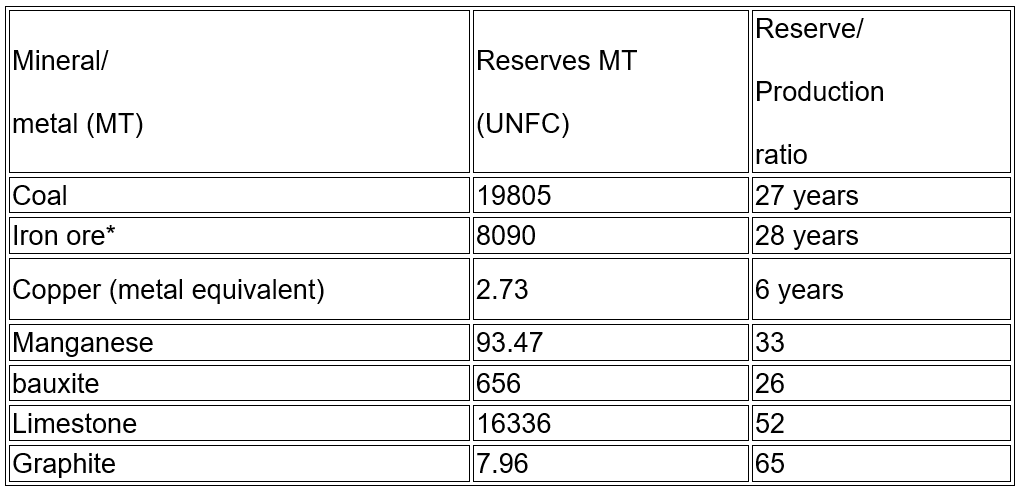

As far as India is concerned, there is little realisation in the government that we have limited mineral resources compared to our increasing domestic demand. The degree of self-sufficiency in minerals is best measured by the reserve-to-production (R/R) ratios of important minerals. The R/R ratio shows how long our mineable reserves could last at the present annual production levels. The following Table provides an assessment on these lines.

*58 MT of Iron Ore is exported annually

These figures are obtained from the publications of the Indian Bureau of Mines (IBM) as per the United Nations Framework Classification (UNFC) which takes into account the mineability and the economics of mining. The R/R ratio declines, as the annual domestic production level increases. Since the production levels of all minerals are bound to increase in the coming years, the deposits for each mineral will last less than what the above estimates suggest. Considering that each of these minerals will get exhausted within the foreseeable future, our future generations who have a stake in it will be the losers. It is imperative that we put in place a policy that shifts emphasis from supply-centric planning to a planning approach that addresses the end-use efficiencies for the different metals, their recycling, their substitution etc. It is also imperative that the policy sets upper limits on annual levels of mineral extraction to make sure that we do not exhaust them sub-optimally. The choice of the time frame, to some extent, depends on the importance that the present generation gives to the future generations.

Simultaneously, emphasis should also be on new exploration effort that will not only add to the discovered reserves but also convert the “probable” mineral deposits to “mineable” resources. This is best measured in terms of the reserve-replacement ratio (RRR), representing the ratio between the number of tonnes consumed in one year, in reference to the number of new tonnes put in place to replace the same. For a given mineral, RRR should remain in excess of or equal to unity, as otherwise we will be exhausting the available resource soon. The national mineral policy should be adapted to take these concepts into account.

The next question is whether it is desirable to permit private control over such scarce mineral resources.

We must recognise the fact that private companies are exclusively driven by their short-term profit maximisation motive. In the case of private mining companies, this is achieved by maximising mineral extraction, irrespective of its long-term implications. Also, private companies, especially in India, where the there is a cosy relationship between the political parties and the mining lobbies, are known to violate the law of the land, causing irreparable damage to the environment, the cost of which rarely gets factored into their profit & loss accounts. That explains the widespread unscientific mining that is going on in several parts of the country and the scars it has left on the environment and on the health of the local communities.

The track record of private mining in India has been dismal for other reasons.

The findings that emerged from the Justice Shah Committee’s reports, referred earlier, revealed multiple statutory violations, including infringement of the mining, the forest and the environment laws, committed by several private iron ore mining companies in different States. In particular, the committee found under-invoicing of large quantities of iron ore exported in one State. For example, in 2011-12 alone, the mining companies exported 38.25 million tonnes (MMT) of iron ore, with the extent of under-invoicing ranging from 30% to 50%, suggesting that thousands of crores of rupees of undisclosed profits were syphoned off to overseas accounts. Such under-invoiced iron ore exports from Goa had taken place since 2003 or even earlier. Some of those companies were regular contributors of funds to the two national political parties, as evident from the contribution reports available from the website of the Election Commission of India.

The fact that the private miners will maximise mineral extraction to optimise their profits comes in direct conflict with the sustainability norm of regulated extraction. Also, short-term profit maximisation, coupled with weak regulation, incentivises unscientific mining and environmental damage which have significant social costs.

Keeping these in view, the balance of advantage certainly lies in favour of social control over minerals, in preference to privatisation.

Of late, there have been several cases of privatisation of the CPSE mining companies that raise concerns from this point of view, as listed below.

Neelanchal Ispat Nigam Ltd (NINL):

The recent near 100% sale of NINL exposes how imprudently the government is going about with CPSE disinvestment. It is reported https://www.livemint.com/companies/neelachal-ispat-nigam-acquisition-tata-steel-long-products-to-raise-rs-13000cr-11644508110874.html) that this CPSE with a captive block of 91 MMT of mineable iron ore resources is being sold to a Tata subsidiary for Rs 13,000 Crores. The potential value of these iron ore resources can be anywhere around Rs 95,500 Crores, if the world market price of $140/tonne for iron ore of comparable quality (~60% iron content) were to be taken as the basis. The economic scarcity value of India’s iron ore resources is far higher. In addition, if the value of NINL’s other land, its plant and equipment and its highly talented manpower is also taken into account, it becomes abundantly clear as to how imprudent has the government been in selling away NINL and losing its control over such precious resources.

Instead, the much larger CPSE, Rashtriya Ispat Nigam Ltd (RINL) at Visakhapatnam, the profitability of which critically depends on a captive iron ore mine being allotted to it, could be asked to take over the NINL to their mutual advantage. The synergy between them could have generated much larger volume of resources for the nation. Ironically, RINL itself, for no valid reason, has also been put on the disinvestment scaffold.

It is relevant here to refer to Para 2.15.4 of the National Steel Policy (2017), which states that “the CPSEs will also be encouraged to take leadership role in development of steel industry”, which runs counter to what the government is doing in the case of NINL. The left hand of the government does not know what its right hand is doing!

Auction of coal and other mineral blocks:

The Ministry of Coal has auctioned more than a hundred coal blocks containing about 5.6 billion tonnes of geological reserves (https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1785444). According to a statement made by the Coal Ministry recently (https://www.ndtv.com/business/42-coal-mines-auctioned-till-date-for-commercial-use-government-2764567), so far auctions in respect of 42 coal mines, with a peak annual production level of 86.4 million tonnes, have been finalised.

At a time when the rest of the world is moving away from coal, this will push up India’s coal production to unprecedented levels, reducing the life of the mineable reserves and increasing the country’s dependence on imports in the very near future.

Most of the coal blocks and the other mineral blocks are located in dense forest areas of Chattisgarh, Jharkhand etc., forming part of the catchments of several important rivers that meet the irrigation and drinking water needs of the downstream population. Upstream mining not only depletes water inflows but also causes pollution. If the adverse implications of this were to be considered, the net social benefit of mining would either be marginal or even negative.

In addition, these coal blocks are largely located in tribal areas notified under the Fifth Schedule to the Constitution, where two important Central laws, namely, the Panchayats (Extension to the Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 and the Scheduled Tribes And Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition Of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 are applicable. Under both these laws, the local tribal Gram Sabhas have special powers to decide on matters such as mining. Unfortunately, the Centre and the States have ignored this altogether, while unilaterally going ahead with the privatisation of mineral blocks. Prima facie, what the government is doing is legally not acceptable, but the greed for political power can drive the ruling elite into self-serving ideologies and decisions that may not necessarily subserve the public interest.

The curious case of privatisation of Beach Sand Minerals:

The beach sands along the coastal stretches of Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Kerala have valuable minerals such as ilmenite, rutile, zircon, monazite, sillimanite and garnet, the first four of which have been categorised by the Dept of Atomic Energy (DAE) as “prescribed substances” (“atomic minerals“) for use in production of atomic energy and for related R&D activities. Monazite, of which India has 7 million tonnes in the beach sands, is the raw material for thorium, which is central to DAE’s long-term nuclear development programme. India’s monazite resources are among the largest in the world and therefore many countries are eager to exploit the same for their respective domestic nuclear development activities, which could hurt India’s long-term interests in many ways.

During the British rule in India, export of some of these atomic minerals started as early as in 1922 and went on unhindered till we got Independence. Whichever atomic mineral is extracted/refined/traded, it is bound to contain some proportion of monazite, which is the raw material for producing thorium.

Soon after Independence, Prime Minister Nehru who had a vision of the importance of atomic energy for India and who took the initiative to set up the atomic energy commission with the range of facilities associated with nuclear power development, banned trade in Monazite in view of its strategic value, on Dr Homi J Bhabha’s advice. In 1950, DAE set up its own PSU, Indian Rare Earths Ltd. (IREL), to undertake mining of these atomic minerals, largely for domestic use, especially R&D in atomic science.

The ban imposed on export of atomic minerals remained in force for more than five decades till the then UPA government in its first term caved in to external pressures, as a result of which the DAE, in January, 2006, excluded ilmenite, zircon, rutile. sillimanite, garnet etc. from the banned list, which implied that private companies could thereafter handle the minerals without having to seek clearance under the Atomic Energy (Working of the Mines, Minerals and Handling of Prescribed Substances) Rules, 1984, though private trade in Monazite continued to be banned.

Since these liberalised minerals, once processed, would still contain some proportion of monazite as an impurity, it is difficult to monitor and regulate the quantities of monazite exported surreptitiously as a part of the other mineral export consignments, despite the DAE imposing a low ceiling on the monazite content of the export consignments. The tailings of these minerals released after processing the mineral sands are rich in monazite and they are expected to be stored under surveillance of the Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB). In practice, however, AERB’s oversight remained fragile, giving scope for the private miners to get away with clandestine export of monazite. There used to be a system of “monazite test certification” for screening atomic mineral export consignments at the ports but, once again, under external pressure, the DAE had done away with it in 2007, which made it easier for the private companies to export monazite as a hidden impurity in the other atomic minerals.

As a result of the PILs filed by concerned citizens and, in one instance, the judiciary itself taking suo moto cognisance of the possibility of Monazite being exported illegally, the DAE and the Union Ministry of Mines woke up from their slumber and ensured that all private licenses for extraction and trading of atomic minerals were revoked in March, 2019. Those who were plundering Monazite till then knew that they could lobby once again for reviving the private licenses.

Perhaps, this was the trigger for the NDA government reviving a proposal to permit private extraction and trading of beach sand minerals containing the banned atomic minerals, as evident from a news report that this item would be included as a part of the 60-Point Action Plan of the Prime Minister (https://indianexpress.com/article/india/sand-minerals-mining-modi-govt-private-sector-7585816/).

While Finance Minister’s 2021 Budget Speech categorised Atomic Energy as a “strategic sector” for the purpose of disinvestment, the above narrative shows how bits and pieces of this strategic sector are being surreptitiously privatised.

CPSE lands:

The 2021 disinvestment policy specifically seeks to monetise the “non-core” lands of the CPSEs. This betrays a total lack of appreciation on the part of the government of the legal provisions that prohibit the alienation of such lands to private parties. Most of these lands were acquired under Section 3(f)(iv) of the 1894 land acquisition legislation, which defined the term “public purpose” as “ ….for a corporation owned or controlled by the State”. Land was acquired at that time from the original land owners on the solemn assurance that they were meant for a company wholly owned and controlled by the government. Any change in the ownership of the land in favour of a private company at a later date would therefore be prima facie illegal. In that event, the lands in question should revert to the concerned States, who handed over the lands to the CPSEs at nominal rates or the land owners to whom false assurances were given. The Centre therefore cannot take unilateral decisions on this. Since it was the States that helped the Centre in setting up the CPSEs and develop the necessary auxiliary industrial clusters around them, they have a direct stake in the CPSEs. These are matters that ought to have been a subject of discussion both in the Parliament and in the State legislatures.

By taking unilateral decisions on the CPSEs, the Centre has certainly crossed the lakshman rekha of federalism.

The LIC IPO:

The LIC which is a household name in India for life insurance is the largest provider of social security cover in the country, for millions of disadvantaged households, spread over rural areas and reaching out to remote areas. While it is these policy holders who have contributed to the enormous wealth of the LIC, with negligible contribution from the public exchequer, DIPAM is proceeding at a break neck speed to disinvest it to a handful of affluent, speculative stock-market investors, including foreign investors, handing over the country’s trillions of rupees of hard earned household savings to them, triggering for the first time a radical shift away from LIC’s original charter of being a social security provider. In the days to come, the LIC’s future will be decided by the unsteady stock-markets, both domestic and overseas, not by the policy holders’ interests. The policy holders who are the largest stakeholders in the LIC find themselves relegated to the background, nowhere to be mentioned in the proposed disinvestment exercise, except being thrown a few negligible crumbs by way of a highly restricted 10% investment window. With the kind of bids that will emerge for LIC’s equity on offer, low-income policy holders and others will get excluded from taking advantage of the IPO. IRDA is statutorily required to protect the policy holders but it would have surely come under the Finance Ministry’s undue pressure to pass the deficient draft IPO documents. Meanwhile, the Finance Ministry has made sure that the IRDA itself remained headless for more than nine months! SEBI which is required to protect the integrity of the stock-markets may also come under a similar pressure. One should not be surprised if the LIC soon loses its pivotal position as a social security provider.

Farm Bills and Bill to further amend the Electricity act of 2003:

In a wholesale privatisation frenzy, no sector of the economy is spared. Wherever there are profitable activities, as it is to be expected, they are given to private oligarchs.

Both the farm bills and the electricity bill would have provided such a further opening to the big business houses to enter agriculture and the electricity distribution sectors, but for the united resistance put up by the farmers’ associations and the civil society. One should not be surprised if the NDA government quietly brings back these bills, once the Punjab and the UP elections are over. Meanwhile, the Centre is privatising the DISCOMS in the Union Territories, which are under its direct administrative control. This provides a pointer to the speed at which the NDA government is going to privatise the economy.

Monetisation of public assets:

The Niti Ayog and the Finance Ministry have already started the process of monetisation of public assets, another avenue for handing over the nation’s wealth to a few chosen business houses. Soon, those business houses will control crucial links in the lifeline of the nation, such as oil pipelines, high voltage transmission towers and transmission lines, food-grains storage warehouses and what not. It is nothing but cherry picking by the oligarchs, leaving the unremunerative parts of an integrated system to be handled by the hapless public utilities and the CPSEs. This will rob the public sector of their capacity to cross-subsidise the disadvantaged sections of the population.

The Chairman of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, Rod Sims is reported to have called for curbs on state and federal government privatisations in Australia, saying the public has lost trust after seeing prices rise following asset sell-offs. Rod Sims said, “assets that governments are earmarking for sale should either have to pass a competition assessment before being sold, or otherwise face regulation if they have significant market power. While monopolies including gas pipelines, electricity networks are regulated, others such as airports and ports are not. (https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/jul/30/prices-going-up-competition-watchdog-tells-governments-to-limit-asset-sales-as-public-loses-trust). Australia’s experience with asset monetisation has been unsatisfactory. India should learn lessons from the Australian experience, rather than trying to please its corporate cohorts.

Going back to the East India Company days:

What the NDA government is consciously doing is to increase concentration of wealth among a few influential business houses and widen the income disparities in the society, robbing the poor further, to enrich the oligarchs. If this process continues long, we will soon revert to the erstwhile East India Company days, pushing back the hard-earned independence of the country into the hands of a few influential business conglomerates.

It was the Greek philosopher, Aristotle (384–322 BC) who coined the term, “oligarchy” to mean rule by the rich. While this term has been in extensive use in describing corporate dominance of the political system in several countries, interestingly, it was the German-born Italian sociologist, Robert Michels, who put forward the so-called “iron law of oligarchy” in his 1911 book, Political Parties, in which he argued that oligarchy is inevitable as an “iron law” within any democratic organisation as part of the “tactical and technical necessities” of the organisation. Michels’ theory states that all complex organisations, regardless of how democratic they are when started, eventually develop into oligarchies. Michels observed that, since no sufficiently large and complex organisation can function purely as a direct democracy, power within an organisation will always get delegated to individuals within that group, elected or otherwise. Using anecdotes from political parties and trade unions struggling to operate democratically, to build his argument, Michels addressed the application of this law to representative democracy , and stated: “Who says organisation, says oligarchy.” He went on to state that “Historical evolution mocks (at) all the prophylactic measures that have been adopted for the prevention of oligarchy.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Political_Parties)

One can only hope that India will not degenerate into yet another example of a democracy slipping into the hands of a few oligarchs. Such a hope lies in the vitality of India’s civil society, that will and should act against any such process.